|

Dear seniors,

Congratulations, it’s been quite the year! You all have accomplished so much and been through so much together that it’s hard to remember it all. Balancing classes, giving senior speeches, playing sports, performing shows, making college applications, socializing with others—the list of achievements is endless. In a survey conducted by the Herald asking students to use one word to describe your class, one sticks out among the rest: community. Undoubtedly, our school has the foundation for having a strong community, but you seniors have expanded this to a level beyond. Not only have you become overachievers and leaders in our community, but you have worked together and alongside one another forming unbreakable bonds. As the school year comes to an end, we will miss you dearly and we will never forget the lessons you have taught us. Because of you, we have not only formed a community, but we have truly become a family. Whatever the future holds, we wish you the best, and no matter what happens, we are beyond proud and grateful for all you have done. Love, The Herald

0 Comments

“The Class of 2024 stands out to me for their ability to build community -- across grades and divisions, and across our region and the world. I will miss them dearly for their strong leadership, for their many talents - academic, artistic, and athletic -- and for their deep devotion to North Cross School. They have been all in this year as senior leaders, and I will never forget them.” -- Head of School Armistead Lemon By Ally Stone

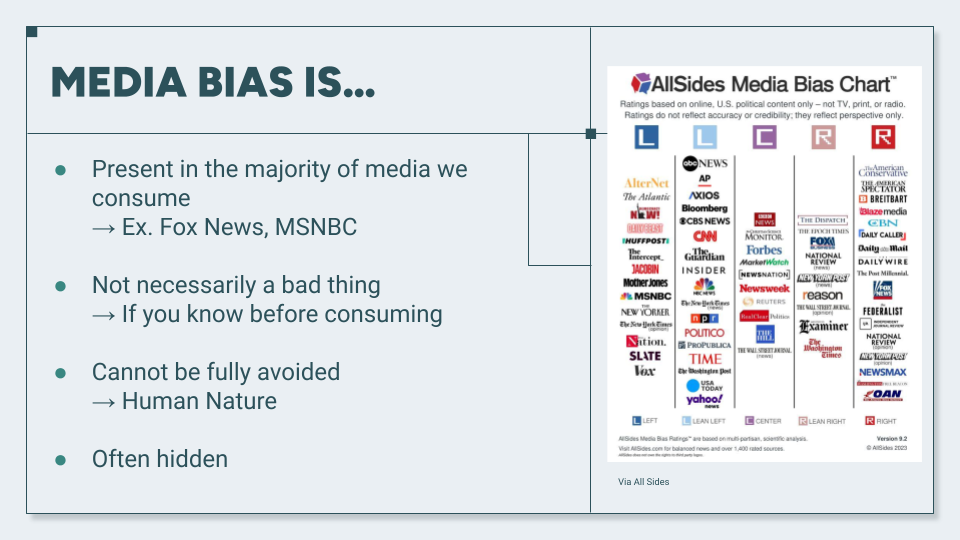

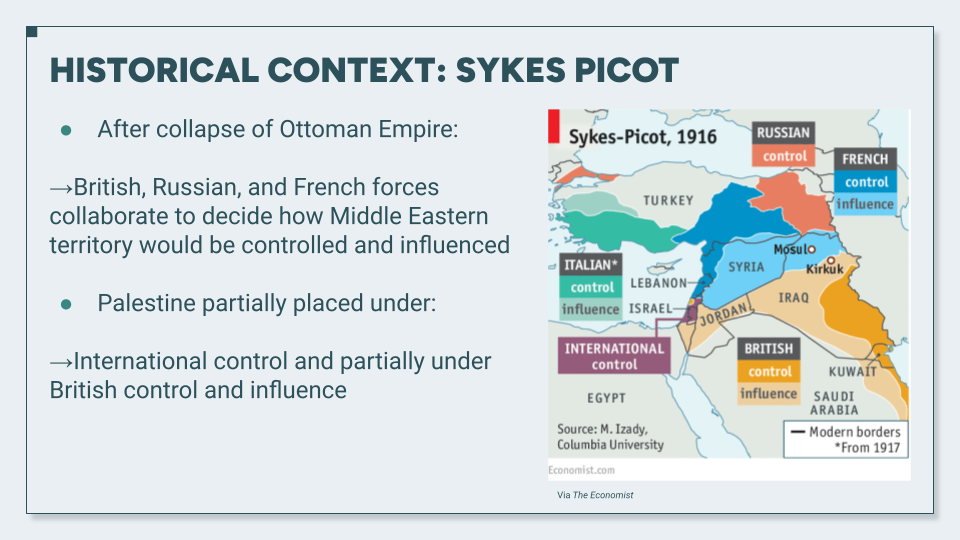

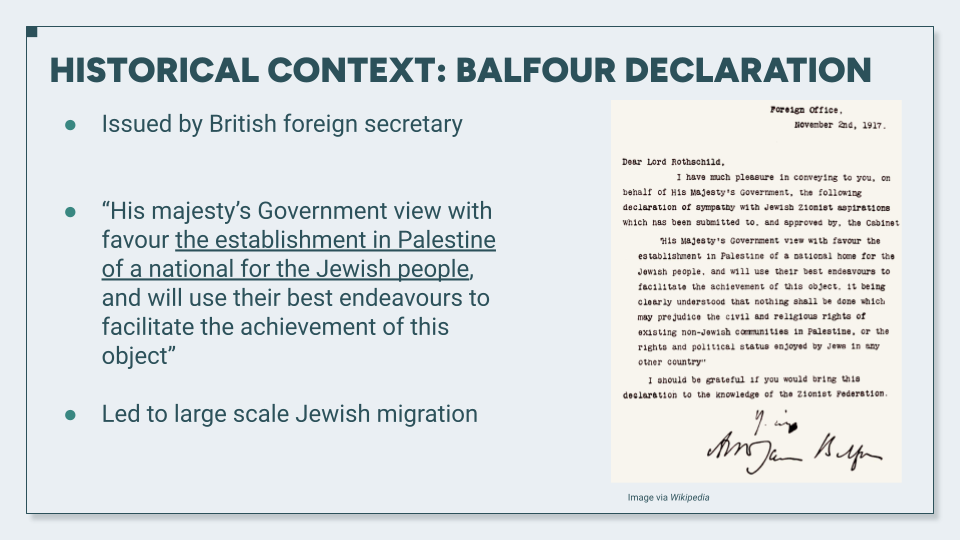

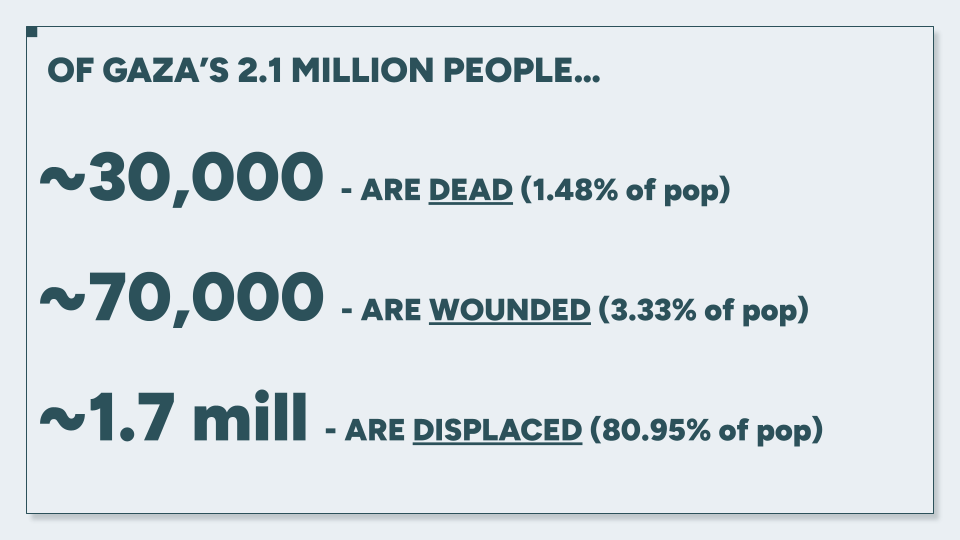

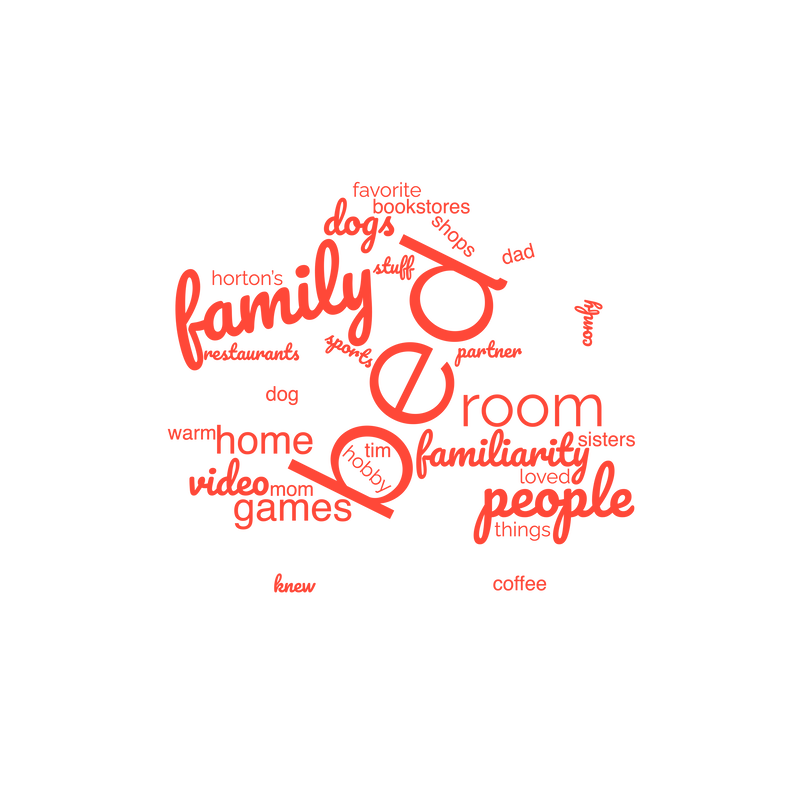

When I attended elementary school in Coral Springs, Florida, we weren't allowed to say the word “gay” in school, and when we asked why, no one explained. They just said, “Don’t say the word ‘gay’. Just don’t say it!” So anyone could suddenly get in trouble for saying the word “gay” with your teachers, but no one knew why, and no one could tell us. Not even school guidance counselors. It was weird. I was fascinated, and that’s what led me to the subject of book banning. Book banning and word banning are an ironic contradiction in the public education system. After all, these words and books are not curse words. The basic building blocks of education start with understanding words and reading books, right? The purpose of reading a variety of books is to instill a sense of empathy for different perspectives. Schools that are trying to teach diversity may use literature with history to give students perspectives from minorities in particular that are targeted by religious groups or those in power. So what happens to public school education if minority perspectives are excluded from general studies? What will the impacts of removing diversity be from our schools? “Books should not be banned in general,” British Literature teacher Brett Odom said. “Even books that are controversial are important to engage with. They broaden our minds. And it's important for us to understand other perspectives even when they're ones we object to.” Surprisingly, parents are most generally behind book bannings in the United States. In 2022, Governor Ron DeSantis signed a law called “Parental Rights In Education”, which has been nicknamed the “Don’t say gay” law. This law prohibits educators from talking about sexuality and gender in the classroom. Ever since the 1600s, Americans have been banning books, such as 1984 by George Orwell. 1984 is one of the most banned books in the U.S. and possibly one of the most banned books in the world. The story is about characters living under authoritarian rule, how they have to live day to day under surveillance and how this oppressive government tries to control their day to day behaviors. This plot line may challenge the ideas of those in power that are actively trying to implement similar laws. By banning books that make us think, America has become dangerously accustomed to the idea that thinking and dissent should not be encouraged. This seems counterproductive to what the American public education system should be providing at the most basic level–critical thinking. Book banning is a form of censorship. It occurs when private individuals, government officials, or organizations remove books from libraries, school reading lists, or bookstore shelves because they object to their content, ideas, or themes. In America 2024, the practice of book banning is alarmingly on the rise. Should Americans be worried? Some frequent [recent] reasons why books are being banned in America is because of LGBTQIA+ content, racism, political views and so much more. Even though freedom of speech is one of the first amendments to the Constitution, book banning makes you question the irony of our foundational laws. Florida is one of the states that bans the most books, just behind Texas. According to a recent 2024 ABC News article titled “Book Ban Lawsuit Moves Forward As Florida District Removes Over 1,000 Titles,” more than 2,800 books have been banned in a Florida county. A lawsuit challenging book bans in Escambia County, Florida, is saying that the removal of books violates the First and Fourteenth amendments. Several authors including David Levithan (author of Two Boys Kissing, Boy Meets Boy, Hold Me Closer, and Full Spectrum), George M. Johnson (author of All Boys Aren't Blue) and Ashley Hope Pérez (author of Out of Darkness), are all backing the lawsuit that challenges the Florida county lawsuit. According to the lawsuit, books that were by or about people of color or part of the LGBTQ+ community, were targeted in the book banning policies described in the lawsuit. Book banning is not limited to the current American political climate either. It happens all over the world. The People’s Republic of China, Nazi Germany, North Korea and The Soviet Union are all examples of governments that have practiced book banning. The censorship of diverse and dissenting ideas may have been the greatest threat to these regimes. Historically speaking, book banning has been an instrument of authoritarian rule under controlling regimes such as Nazi Germany or North Korea to prevent citizens from accessing dissenting ideas. This should be a reminder to Americans that reflecting on the past will give harsh clues to the future.  By Caroline Welfare Opinions Editor Earth Day there are 24 hours each spring when everybody is reminded to keep good habits and conserve energy. But our leaders don’t do a good enough job of telling us why we should care or what we should do. How are all animals important in the great circle of life? How will the scars we leave now come back to bite us later? Yes, it’s important to turn off the lights when we leave the house because it saves energy, and overuse of resources is interfering with the planet’s natural patterns, but with more and more of our lives spent online, it becomes easier to question why we need to do this. Beyond that, the lack of communicating and spreading environmental awareness is making people unaware of what to do when the unwanted side effects of woodland creatures are thrust into their faces. The lack of information can also lead people into potentially dangerous situations. Who hasn’t heard their parents complain about the raccoons getting into the trash? Or pigeons (and seagulls… and crows…) trying to steal their food? More and more wild animals are getting pushed into the cities, and are adapting to survive. And while it’s great to see more of them surviving (coyotes have been seen looking both ways before crossing the street), it also means that we are being confronted with new problems, namely, aggressive animals, pests carrying diseases, gardens getting eaten, raccoons that can open trash cans, and predators capable of injuring our pets. However, there are some other considerably worse side effects of being in close quarters with wild animals. Sometimes the consequences of not respecting them has something to do with eating something or being eaten. CBS news recently released an article about people getting sick and dying from eating a delicacy in Zanzibar: sea turtle meat. Not only is this sad for the sea turtles, it’s also a miserable thing to go through as the consumer, as the list of symptoms is “all of them”. People being unaware of these sorts of dangers can get hurt, as shown in the more extreme example of the early 1900s Maneater of Champawat; an injured tigress that claimed an estimated 436 human lives. It was finally stopped in India in 1907 by famed tiger hunter and conservationist Jim Corbett, the India Times said. In the book No Beast So Fierce, it is explained that the tigress had been maimed by a poacher’s bullet early in life, and was left unable to hunt its usual prey. As the East India Company pushed farther into the forests, its encounters with humans became more frequent, with us becoming its main food source. What stings the most is that both of these sufferings were entirely avoidable, if people had been responsible in their resource use and not tested their luck with a questionable delicacy. While those are somewhat (actually, they are) very unpleasant examples, their message rings true: People need to know and respect the boundaries of nature, for our safety, and everyone else’s. Earth Day is a prime opportunity to remind ourselves of what we can do to help, but what we do on Earth Day should carry over into every other day of the year. There is a reason that the image of a quiet mountaintop with a cool breeze and a warm sun nurturing blooming flowers is an idyllic image in our minds, and the day that we forget that, we have to protect that for ourselves and our future is a dark, scary day indeed.  Photo by Eason Zhou Photo by Eason Zhou In an ideal world, all of the news coverage and reporting we consume would be a fair account of the events that occur. Journalists would inform the reader of the conflict at hand, provide ample context, and then provide perspectives from both sides of said conflict. Unfortunately, we live in a world where media bias is, more often than not, present in the media we consume. In times of global conflict and massive loss of life it is the responsibility of the press to report from an angle that presents both sides, that provides context to these issues, and that does not use grammar as a weapon against any group of people. This has not been the case for the Israel-Palestine conflict. The United States’ media coverage of the Israel-Palestine conflict since the state of Israel declared war on Palestinian militant group Hamas, has not been presenting readers with a fair view of the Palestinian civilian’s side, instead showing a bias towards the state of Israel. The U.S. media has shown its bias through the diction chosen to inform readers of events that have taken place, the consistent usage of the passive voice to remove Israel from its atrocities committed in Palestine, and the disproportionate coverage of Palestinian death as compared to Israeli death. The presence of this bias in reporting inhibits the reader’s ability to make informed decisions, or to consume media in which factual information is the main focus. Media bias is defined by All Sides as “The tendency of news media to report in a way that reinforces a viewpoint, worldview, preference, political ideology, corporate or financial interests, moral framework, or policy inclination, instead of reporting in an objective way.” The responsibility of the press is to provide us with information, not to feed us a narrative that we then instill in our minds. Despite this, media bias is present in the majority of the media we consume. Think Fox News, which gives biased reporting in favor of the right side of the American political spectrum, or MSNBC, which is biased to the left side of the American political spectrum. Media bias cannot be fully avoided since humans often process information and report from our own standpoints and partialities, and it’s important to remember that media bias is not always a strictly bad thing. What is more dangerous than clear bias, is hidden bias, defined by All Sides as a type of bias that “misleads, manipulates, and divides us.” Our ability to make informed decisions directly relates to how much context we receive on the topic at hand. So, allow me to explain, in the best way I can (in an 18 minute speech), the history behind the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. With the fall of the Ottoman Empire, French, British, and Russian forces came together to discuss how the territory in the Middle East would be influenced and controlled, in a negotiation known as the Sykes-Picot agreement. Sykes-Picot allocated various Ottoman territories to the French, British, and Russian, Palestine, being placed partly under international control, and partly under British control. Concurrently, the British foreign secretary issued the “Balfour Declaration,” which expressed support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” The British Mandate supported the widespread migration of Jews to Palestine, because of a new movement in Europe called Zionism. The University of Michigan says the goals of Zionism are “all Jews constitute one nation (not simply a religious or ethnic community) and that the only solution to anti-Semitism is the concentration of as many Jews as possible in Palestine/Israel and the establishment of a Jewish state there.” Even though this is a belief held by many members of Judaism, it is not held by all Jews. Furthermore, those who are opposed to Zionism are not inherently anti-semetic, and being opposed to Zionism does not warrant senseless anti-Semitism. It is important to mention that Zionism’s origins come from the continuous persecution of the Jewish people, and the belief that the Jewish ancestral home is where Israel was established. However, the establishment of the state of Israel conflicted with what the British forces had promised Palestinian peoples, independence and a right to govern their own land. The British had been making agreements with both the Palestinians and the Zionists, the British gave the Zionists the right to create a state on the land, the state of Israel. The suffering and persecution faced by the Jewish community throughout history is not something I intend to excuse, and while the Jewish people had an absolute right to flee active violence and genocide against them, the displacement of other ethnic communities after the creation of the state of Israel would have consequences down the road. The State of Israel was established on May 14th, 1948, which immediately sparked the first Arab-Israeli War. Palestinians refer to this time as “Al Nakba” or “The Catastrophe” because during this year 75% (per Institute For Middle East Understanding) of Palestinians were forcibly expelled from their homes and left displaced. This first war ended in 1949 with a victory for Israel, divided the land into three parts, the state of Israel, and the Palestinian territories of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Militant and political movement group Hamas has maintained control over the Gaza Strip since 2006, when the group won the Palestinian Authority’s parliamentary elections, and shortly after the group violently took over the Palestinian Authority. Hamas’ violence against civilians and the state of Israel has led to the group’s designation as a terrorist organization by the United States, the European Union, Japan, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Hamas’ carried out their most recent act of terrorism on October 7, 2023. During the attack Hamas launched over 5,000 rockets into Israel, killing about 1,200 Israelis and taking 253 hostage. Israel responded by declaring war on Hamas, launching air attacks and ground invasions. Since this declaration of war, the Israeli Defense Force have killed about 31,000 Palestinians, and left 70,000 injured, per AP News. Additionally, Israel ordered all Palestinians who live north of Wadi Gaza to leave their homes and travel south, leaving 1.7 million Palestinians displaced, per Congress Research Service. The population of Gaza is 2.1 million, meaning 1.48% of the population has been killed, 3.33% of the population is currently injured, and 80.95% is currently displaced and without a home. Now, let’s discuss the media that much of the American public and residents consume and the ways in which it shows bias towards Israel in its reporting. Language rules the world of news. Journalists are well versed on which words evoke what emotion in readers, they know that diction plays a large part in what their audience takes from the reporting. In the month after Hamas’ October 7th attack, The Column, a media criticism and political analysis substack, published “‘Massacred’ vs. ‘Left to Die’”, a quantitative analysis which documented media bias against Palestinians. The researcher who collected this analysis has remained anonymous, so going forward, I will be referring to the researcher as “Otto” as that is the pseudonym he published his findings under. The portion of this research that I’d like to discuss is Otto’s third finding: That the word “massacre” was used by CNN, FOXNEWS, and MSNBC in 30 second segments more to refer to the 1,200 Israelis killed by Hamas on October 7th, than the 11,000 Palestinians killed by the Israeli army between October 7th and November 7th. FOX NEWS used “massacre” as committed on Israelis 770 times, and committed on Palestinians nine times. CNN used the term 503 times for Israelis, and 53 times for Palestinians. Finally, MSNBC used “massacre” 382 times as committed on Israelis, and 16 times as committed on Palestinians. Interestingly enough, the analysis shows that the term “massacred” was only used to describe Palestinian killings when 1) A Palestinian was directly interviewed, 2) When an advocate for Palestine was interviewed, or 3) It was prefaced by the statement by the reporter, commentator, or news station as “…what is being called a massacre.” In an opinion article in The Washington Post entitled “A silent desperation on the slow march out of Gaza City” by David Ignatious, writes: “This war has produced deeply horrifying images: Israeli children assaulted in barbaric ways by Hamas terrorists; Palestinian children left to die under Israeli bombardment” The choice of wording here is interesting. While Israeli child victims are “assaulted in barbaric ways by Hamas terrorists,” Palestinian children are simply “left to die”? Who are we to assume “left them to die”? Their parents? Based on the fact of the events, it would appear that Palestinian children too are being assaulted in barbaric ways. Israel is air striking their homes daily, causing them to be buried under the rumble of explosions, they are starving to death because Israel is not allowing shipments to come though Palestinian borders, and IDF soldiers continue to kill and fatally injure Palestinian children with every ground invasion they conduct. It’s not that Palestinian children are not being “massacred” or that they are being “left to die” it’s that these media outlets are able to choose specific words to present whatever information or opinion they wish to present, skewing our own view of the topic. According to Otto’s research, the US media is using the English language to change our view of this conflict in favor of Israel. Media outlets should be using words like “massacre” for atrocities involving both the IDF and Hamas, and that when media outlets choose to utilize different words for different parties, we should be able to recognize that and identify that these media outlets are biased. Now, let’s dive into the usage of the passive voice during reporting on the Israeli-Hamas War. There are two main grammatical voices used in writing, the active voice and the passive voice. Purdue University defines the active voice as “the grammar structure in which the subject comes before the object in the sentence and shows a direct action on the object in the sentence,” and then defines the passive voice as “the grammar structure in which the object comes before the subject in the sentence, thus making the action indirect,” Typically, the active voice is preferred in journalistic writing because it is more action driven, concise, and does not leave as much room for ambiguity as the passive voice does. The U.S. media has been utilizing the passive voice to remove Israel as the perpetrator of violent actions against Palestinian civilians. For the Israel-Hamas War, headlines have looked like this one from NBC News: “A group of Palestinian men waving a white flag is shot at, killing 1,” This headline is misleading, because the headline implies that NBC News does not know who shot at the Palestinian man, and who shot and killed one Palestinian man. A witness to the shooting, Ahmed Hijazi, told NBC News that the bullets came from the nearby Israeli tanks “lining the road,” Another recording angle of the shooting corroborates Hijazi’s statement, however NBC News has not changed the headline, and the question of “Who shot the men?” remains unanswered at first glance. Perhaps the most frustrating part of the usage of passive headlines during this conflict is that headlines grab readers attention and encourage them to click or not click on certain articles. If a reader decides to not click on this article after reading then their only impression will be that while yes, a Palestinian man was killed, it is not clear who did it and readers will not understand that there was intent behind his murder. When the IDF was contacted about the shooting, a spokesperson said that they were “not aware” of the shooting and that the footage was “clearly edited” Other examples of the usage of the passive voice, which are all from the New York Times, to avoid holding Israel accountable for its actions include: “Lives Ended in Gaza,” this headline does not mention by who, nor that Palestinians’ lives are not simply ending, but that they are being killed or starved to death by the IDF, “Crowded Gazan City Bombed as Negotiators Try to Revive Cease-Fire Talks,'' The headline does not address who bombed the “crowded Gazan city,” although it is incredibly apparent, as there is only one nation that continues to drop bombs on the Gaza Strip. Finally, “He Loved Basketball and Wanted to Help His Family Stores. A Bullet Ended It All.” While this headline is well crafted, it does not mention that seventeen-year-old Tawfic Abdel Jabbar’s life did not simply end in a bullet gone awry, but that he was shot and killed by Israeli Defense Forces. Headlines like these clearly show that even when these media giants know who is to blame for the killing of Palestinians, they do not want to outwardly state that Israel is behind it. This shows that our media intentionally picks and chooses what to outwardly tell us, hiding behind the passive voice. Articles like this one entitled “Israel Strikes Major Gaza Hospital Killing 4 Wounding 17” published by Voices of America clearly state that Israel was in fact the entity responsible for the air strike, and there is no real room for speculation based on the title alone. There is no excuse for killing, even during times of conflict, and there is no individual who deserves to be reduced to a number on a list of casualties. That being said, there is still an issue when the media prioritizes showing the public the casualties of one group over another, especially when there is a significant gap in the number of casualties. An article in The Intercept entitled “COVERAGE OF GAZA WAR IN THE NEW YORK TIMES AND OTHER MAJOR NEWSPAPERS HEAVILY FAVORED ISRAEL, ANALYSIS SHOWS” by Adam Johnson and Othman Ali presents quantitative data gathered from the first six weeks of the Israel-Hamas War from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times. The two analyzed over 1,000 articles in order to gather statistical evidence which showed that major media companies had a bias towards Israel during its coverage of the war. Johnson and Ali found that in articles from The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times from October 7th 2023 - November 25th 2023, “For every two Palestinian deaths, Palestinians are mentioned once. For every Israeli death, Israelis are mentioned eight times — or a rate 16 times more per death than of Palestinians” meaning that even though Palestinian deaths were outpacing Israeli deaths, Israeli deaths were getting more coverage than Palestinian deaths. Not only did their research identify this, but it established that even as the Palestinian death toll rose, the mentions of Palestinian deaths fell. The Stanford Cable TV News Analyzer, which the Brown Institute for Media Innovation calls “ an interactive tool that gives the public the ability to not just search transcripts, but also compute the screen time of public figures in nearly 24-7 broadcasts from CNN, Fox News and MSNBC,” identified a similar trend in cable news media. From October 7th, 2023 to November 25th 2023, The SCTVNA found that the words “Israelis” and “dead” were spoken on CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC in a total of 37 clips and a combined 51 seconds. The SCTVNA then found that between the same dates the words “Palestinian” and “dead” were spoken on the same networks in a total of 17 clips and a combined total of 20.4 seconds. From October 7th, 2023 to November 24th 2023, OCHA estimated that about 14,800 Palestinians were killed over the course of the war and 1,200 Israelis were killed over the course of the war. Again, it is not that the Israelis who were killed by Hamas on October 7th or over the course of the war should not receive media coverage, this research only establishes that the Palestinians killed by IDF air strikes, IDF ground bombardment, and starvation are not getting anywhere near the same amount of coverage, even though their death toll was over 10 times the Israeli death toll. As I enter my conclusion, it is important to establish why the U.S. media is doing this: because it is in their best interest to do so. Because media giant Fox News has a heavily right wing audience, it has to keep up the expectation that it will appeal to its audience's views. According to a poll conducted from November 27th - December 3rd, 2023 by Pew Research on whether or not Israeli is “going too far in current military operation,” the results found that 34% of Republicans said that Israel is “taking the right approach” 25% saying that Israel is “not going far enough” 12% saying that Israel is “going too far” and 29% being unsure. Fox News has an audience to retain, and the reporting that they are carrying out, in their eyes, does not always have to be representative of what is truly happening in the world, it just has to maintain their audience. In the same poll, Pew Research found that 45% of Democrats said that Israel is “going too far'' 18% said that Israel was taking “the right approach” 8% said Israel was “not going far enough” and 29% were unsure. Left leaning media outlets like CNN and MSNBC do not heavily favor Israel as much as right leaning media outlets, but they have shown support for President Joe Biden and his efforts to aid Israel during this war. As media in the United States becomes increasingly more partisan as the polarization in our country grows, it is important that we understand that these media outlets are not always going to portray events in a manner that presents us with facts and equal coverage, but instead in a way that contorts them to whatever bias or agenda they want to push. As this war wages on, and the death count rises everyday, as of today it stands at 33,077 Palestinians and 1,139 Israelis, it is our responsibility as Americans and citizens of a global community to ensure that we understand how easily our media is able to spread misinformation or use words as a weapon. It is our job to seek news sources that do not have political leanings or reasons to withhold information from us. We do not have to agree with the actions of either party during this war, but we should seek to understand them, and have our own positions. Our thoughts and opinions cannot be taken away from us, and our voices are the most important tools for change we possess.  Word clouds (created by wordcloud.com) of responses to Jan.18 survey question of what students and faculty enjoy about being away from home. The cloud to the left includes responses about what they missed when they were away. Word clouds (created by wordcloud.com) of responses to Jan.18 survey question of what students and faculty enjoy about being away from home. The cloud to the left includes responses about what they missed when they were away. When you think of the word home, what image comes to mind? Chances are you are probably imagining some sort of house equipped with windows, doors, and a roof overhead. It is not surprising that we all share this vision when we hear the word home. In fact, when you go onto any search engine and type the word home, you will find the same familiar houses that come to mind. We all associate houses with homes, but homes are much more than walls of brick and wood. “Comfort,” “Family,” “Security,” “Freedom,” all are different ways to describe home. Home means something different for everybody, but each meaning is important and respected nonetheless. Regardless of what home means to you, the thought of straying away from the familiarity of home can be scary. If you have ever been away from home, I am sure you can agree that after a while of separation, you begin to crave the feeling of being back at home. Even if you tell yourself “you never want to leave or go back,” you will still have a sense of gratitude and ease when you return. Although it is nice to enjoy taking a break, most of us will eventually come back to the homes we know and love. For the 33 international students at North Cross coming from fifteen countries around the world to live in the dorm, their “homes” are thousands of miles away. To put it into perspective, some of these students will only get to see their family or homes only once or twice a year. Our very own Willis Hall Herald editor, Eason Zhou ‘24 has not returned to his home in China for over 800 days. This extension of time might seem unbearable and depressing at first, but there is more to it. Luckily for Zhou and all the international students, their time away from home does not need to be a negative thing. Instead, their new environment has given them the opportunity to form a new home, their “home away from home.” In a new home, our international students can gain a new sense of belonging. Some students have even gotten the chance to stay with and join the homes of their host families. As they will always keep their “old homes” close to heart, they are able to find new meanings and beginnings with their homes here in the United States. Recently, in a survey to find out what international students liked most about their home away from home, we discovered that each student had their own unique outlooks. From “experiences and opportunities” to “pools and having a chance to be away from parents,” all the international students have grown to appreciate something new about their homes here. One of the best parts about homes is that along with having multiple different homes, we can share our home with one another as well. This January, Willis Hall welcomed a new Spanish Teacher into our community. We hope to share with her our love of North Cross, a school and community that is one of the many places we call home.  February 1st, 2024, is National Freedom Day. The date is not significant simply because of its illustrious title of freedom, a revered principle in this great nation, but because of the commemoration of the neverending struggle of liberty for all. On February 1st, 1865, led by Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens, the House of Representatives passed, by a vote of 119 to 56, the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution. The amendment postulates that: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” In layman’s terms, this states that slavery is effectively illegal inside of the territory of the U.S. or anywhere within its authority. It created a new sense of unity in this nation, although there was still an uphill battle to be fought. Still, the landmark decision to change for the good cemented the U.S. as a nation willing to do what is just, moral, and operate on the side of the Right. National Freedom Day has become a beacon of what America stands for. Our fathers set us on a trajectory–a destiny–for prestige and power used for the greater good of humanity. Obviously, I must have a personal connection to this concept of “freedom”. The revered principle of personal liberties is a concept which has unmatched importance. In my journey of life I have found that there is no greater gift, given by the sacrifice of millions throughout our nation’s history, than the right to be fairly represented, treated, and judged. In this nation, and every such nation dedicated to preserving the rights and legal guarantees for all who inhabit them, should be a nation venerated and exemplified on the world stage. My individual connection with egalitarian principles and democratic engagement stems back to my early days of middle school. As you all know, the year 2020 was a turbulent period in not just American, but world history. As I saw even the adults in my life plagued by uncertainty, questioning the future of our planet, I knew that if such an event would happen again, there needed to be someone who could stand up and advocate for the true founding ideals of America. As the year progressed, and the unrest became ever apparent, violence and injustice became the only solution for some. That was a particularly haunting premise for me. Was this nation not founded on liberty and justice for all? Ever since I asked myself that question, I have dedicated my life, studies, and efforts to the furthered sustainability of freedom in the hearts of anyone willing to work towards its survival. We have come a long way since the days of the cataclysmic divide of this country in 1861. However, we must steel ourselves, and rededicate ourselves to the proposition that as long as free men live, not a man shall be a slave. The new generation–this generation–must find what it means to live without fear. We must learn to revere the rights and privileges that we are endowed with from birth, and to hold ourselves as examples for others. As I conclude, I implore you to reflect upon my statement. What freedoms are you guaranteed? What do you want to see change? What is the most ideal life you can live in this nation? If everyone reading were to answer these questions, then there is no doubt in my mind that a more prosperous, successful, and free society would exist in our future years. - Mason Bibby ‘27 Photo by Eason Zhou  By Caroline Welfare In December, diplomats and environment activists assembled in Dubai for the United Nations climate summit. Not many had real hope for progress, with peacekeeping in the Middle East failing and sound geopolitical leadership deteriorating and the chosen host country, United Arab Emirates, one of the world’s petrostates, and the chairman, Sultan al-Jaber, the head of the national oil company. The last one of the three threatened to turn this important event into an exercise of greenwashing. With sighs of relief, the UN’s summit Cop28 defied bleak expectations and brought the world’s nations, most of them, together in an agreement to move away from coal, oil, and natural gas, finite resources that are main fuel sources for global warming. The 198 parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change agreed on a text angling for a transition “in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner” away from fossil fuels. Still, compromises that let down many environmentalists had to be made. The European diplomats hoped to “phase out” fossil fuels altogether, but fossil-fuel producers refused to agree. Small island nations feel their voices were not heard, as the deal determined only “unabated” coal power was to be phased down, leaving dirtier options free to continue so long as the burnt emissions are caught at the source. Pessimists claim that the deal was “politically naive and economically unfeasible. COP operates by consensus, meaning that the big petrostates had veto on any deal” the Economist states. Despite this milestone, fossil fuels are likely to remain prominent for coming decades. Even optimists believe that the battle will continue. However, vast strides were also made. Mr. al-Jaber allowed for climate diplomacy to be stronger than many had hoped for. He proved more concerned with securing a negotiating triumph for the UAE rather than distorting the summit’s process for economical gain. 50 oil companies made early pledges to reduce methane emissions, a powerful, not to mention dangerous greenhouse gas. Many other successes led up to this deal, including the United States and China’s agreement, two of the largest polluters and historic rivals working together to lay the groundwork for this event. Even next year’s summit location - Baku - is seen as “a symbol of harmony”. Larger fossil fuel corporations have seen the warning: because of the financial changes that must be made globally, business will become more challenging and struggling nations will require aid now more than ever, with companies inevitably fighting back. But the bleak progress that still must be and challenges that still must be faced is made dull in comparison for the beacon of hope that COP28 shines for the world. I feel like schools push students to know a lot. There are at least six different subjects taken by an individual student. There is a large amount of homework to do every night as well as reading and extracurriculars such as sports. As well as the much, much needed additive of sleep. There simply aren’t enough hours in the day. I have a hard time getting the right amount of sleep and I know my classmates also have the same problem. I feel that it would greatly benefit attendance and the sleep of the entire student body if all days started at 8:30 instead of 8. I know it is a North Cross tradition, but I suggest that we eliminate morning announcements, unless there is a senior speech as well as shortening the time in between classes to four minutes, because under my current understanding it is five minutes. That should give enough time to start school a little later. So I would like you to take my concerns into consideration when writing the next school paper.

Thank you, Oliver Lacy ‘26 |

Editors:Editor-in-Chief: Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed